How AI slashed 40 years of bureaucracy to six days

And saved one California county from a well-meaning but terrible law.

Bureaucratic procedure is a “cancer,” as Jen Pahlka wrote about in a post I linked to a couple of weeks ago. When it metastasizes, it threatens the entire functioning of government. People on the right are especially exercised about overweening rules, of course, but not only them—to wit, Pahlka, and also Ezra Klein.

And why does it metastasize? Because politicians often have no idea of the bureaucratic ripple effects the laws they pass are going to have.

So at one level, today’s piece is a nice little story about a neat use of tech to solve a gnarly bureaucratic problem. At another level, though, it’s an indictment of the entire process of lawmaking. And maybe, just maybe, it points at a way out.

The TL;DR: In certain cases AI can be a huge help in dealing with the unexpected bureaucratic burdens of new laws. In future it might even prevent legislators passing some of those laws in the first place.

Our story begins more than a century ago with the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans began leaving the South to escape Jim Crow laws and other forms of discrimination. These laws included a spate of race-based zoning ordinances, starting in 1910, that barred Black people from living in white neighborhoods.

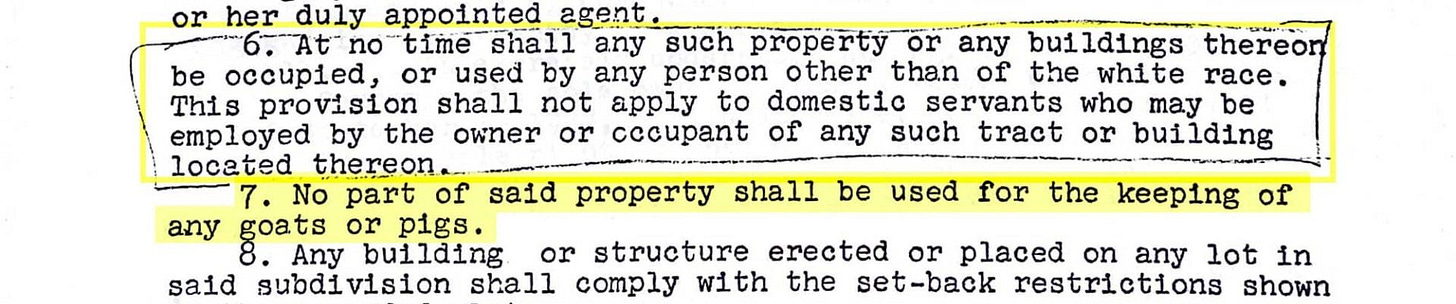

By 1917 a Supreme Court decision, Buchanan v. Warley, had ruled race-based zoning unconstitutional. But it didn’t forbid racial restrictions in private contracts. And so began an explosion in the use of racially restrictive covenants: language in a housing deed that forbids non-white people from owning or living in the property.

In 1926 the Supreme Court upheld the validity of racial covenants—leading to another surge in their use—only to turn around 22 years later and rule them unenforceable. (This, by the way, is a fascinating nugget of legal history, since both rulings turned on the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law. The 1926 ruling said that the amendment doesn’t cover private contracts, but only protects people from discriminatory actions by states. The 1948 ruling agreed, but then—in a nice bit of judicial fancy footwork—said that for courts to enforce such contracts does violate the amendment, since court rulings are “actions of the states.” By such contortions is the long arc of history painfully and begrudgingly bent towards justice.)

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 finally banned racial discrimination in housing altogether. But even after that, some new racial covenants continued to be written. And possibly millions of pre-existing covenants remained in housing deeds, an unpleasant—albeit legally toothless—surprise for prospective buyers.

Eventually, states began passing laws allowing property owners to get racial covenants removed from their deeds. By the end of last year about half the states had such a law.

But California—of course, California!—had to go one better. In 2021 it passed AB 1466, which, among other things, required counties to “establish a restrictive covenant program to assist in the redaction of unlawfully restrictive covenants”—in other words, to start going through all the deeds in their archives and weed out racial restrictions.

Now, I’m not sure why California lawmakers thought this necessary. The state already allowed property owners to get racial covenants deleted, though few ever did. The new law, AB 1466, also made it easier for buyers to find out if there was a covenant on their deed, by requiring title companies, realtors and anyone else involved in a real-estate transaction to tell them if they knew of one.

In other words, there were mechanisms for gradually removing covenants as they came to light. But no: squeaky-clean California wanted to expunge the entire shameful history of racial discrimination from its housing records. And it tasked the 58 counties with doing it.

This is where things unraveled.

Santa Clara is one of the state’s most populous counties, encompassing most of Silicon Valley. It has 24 million property records stretching back to 1850. They consist of over 84 million pages—a pile of paper that "would soar to the height of Mount Everest,” as one news story put it.

The county assigned two employees the job of going through the stack of deeds one by one looking for racial covenants. Their target was to complete the entire 84 million pages in six years. Eleven months in they had reviewed 100,000 pages, 0.1% of the total. It was likely a similar story all around the state.

Enter a team led by Daniel Ho at Stanford University’s Regulation, Evaluation and Governance Lab. In a just-published paper they detail how they teamed up with the county recorder’s office to run the deeds through a large language model looking for racially restrictive wordings. Simply searching for words like “white” would have turned up lots of false positives, while typos and mistakes in optical character recognition made any simple text search unreliable. But LLMs excel at the kind of pattern recognition that overcomes these hurdles.

Ho et al only looked at deeds from 1902 to 1980—racial covenants outside that timeframe were vanishingly rare—but that was still 5.2 million pages. The task, they estimated, would take a human checker more than 40 years at 40 hours a week, and cost $1.4 million at California’s minimum wage. The researchers’ LLM did the whole thing in six days for $258.

(As an aside: The researchers used an open-source model that they fine-tuned themselves. They tried chatGPT as well, but it cost far more and proved less accurate. This matters because it shows government agencies, nonprofits, media outlets, and others need not always rely on companies like OpenAI, which is pretty important for limiting Big Tech’s stranglehold on civil society.)

What they found was that in 1950, one in four properties in Santa Clara had a racial covenant attached. Interestingly, they were also able to identify where and when the covenants were clustered and who were the developers behind them, creating a rich resource for historians. Getting these covenants removed would still be a bureaucratic process, but a far smaller one.

Let’s dwell on this for a second. From 40 years down to six days: decades of drudge work eliminated at a stroke. And this is for one tiny problem in one county. Now scale that up to all the times a thoughtless legislature passes a measure that will entail a huge amount of bureaucracy. What if you could farm out a lot of that bureaucratic work to AI?

Of course, it’s not always going to be that easy. A big part of the Santa Clara project was OCR’ing the microfiched deeds. Stephen Menendian of UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute pointed out to me that especially in smaller, poorer counties, records aren’t even on microfiche yet. “It’s not hard to locate the [racially restrictive] language,” he says. “The hard part is getting access to the file in the first place.”

Still, there’s clearly potential here to help cut through the bureaucracy created by poorly conceived laws. But maybe the more exciting possibility is to prevent such laws being passed in the first place.

For example, Ho suggests, you could estimate the bureaucratic burden that a new law or rule would impose on agencies. Or cross-reference a change to the legal code with all the regulations that refer to that code, and estimate the work of updating and implementing them. Perhaps in future—though Ho thinks the models are not there yet—it might be possible to predict clashes between federal and state laws, or between different states’ laws. In any of these cases, legislators could be given that information before they pass a new law.

Of course, most of this is still speculative, and even if it works it won’t solve everything. All lawmaking is political, and legislators will still have reasons to pass laws that don’t make bureaucratic sense. But wouldn’t it be nice if they could see the consequences of their actions, and sometimes even change their minds? I’m still a pretty big AI skeptic, but this kind of application feels compelling.

Links

The time-bomb in the American workforce. Aging population + AI/robots = looming disaster, says newly minted Nobel economist Daron Acemoglu. That’s unless the government follows European examples by training workers in new skills and directing funding towards AI that doesn’t just try to automate people away. (New York Times)

Eldercare on young hackers’ minds. Some people, on the other hand, are taking aging seriously. Three of the five winning teams at a hackathon run by the Singaporean government produced tools to help the elderly with isolation and access to services. (GovInsider)

Twenty-three solutions to youth homelessness. Promising consensus results from a citizens’ assembly in Oregon, which I referenced in a previous newsletter. (DemocracyNext)

Guess who’s best at e-government. Denmark and Estonia (natch) lead the UN’s annual e-government rankings, with Asian, Gulf and European countries also highly placed. The US just barely makes the top 20. Canada is 47th, behind Russia (!), Mongolia (!!), Kazakhstan (!!!) and Argentina (enough said). (UN E-Government Knowledge Base)

But better e-government isn’t enough. The online world is at the stage that industrial capitalism was a century ago, argues James Plunkett, with Big Tech as the robber barons. So rather than just building better digital versions of existing public services, it’s time to ask what social and economic reforms we need—the online equivalents of public health, worker protections, civic spaces, and so on. (Future State)